Ridley Scott's Lost Dune: A 40-Year-Old Secret Unveiled

This week marks four decades since David Lynch's Dune premiered, a box office flop that's since cultivated a devoted cult following. Its stark contrast to Denis Villeneuve's recent adaptations has fueled renewed interest in the project's tumultuous history, particularly the little-known pre-Lynch version spearheaded by Ridley Scott.

Until now, details surrounding Scott's seven-to-eight-month development period remained scarce. However, thanks to T.D. Nguyen's discovery of a 133-page October 1980 draft within the Coleman Luck archives at Wheaton College, we now have access to Rudy Wurlitzer's ( Two-Lane Blacktop, Walker) script.

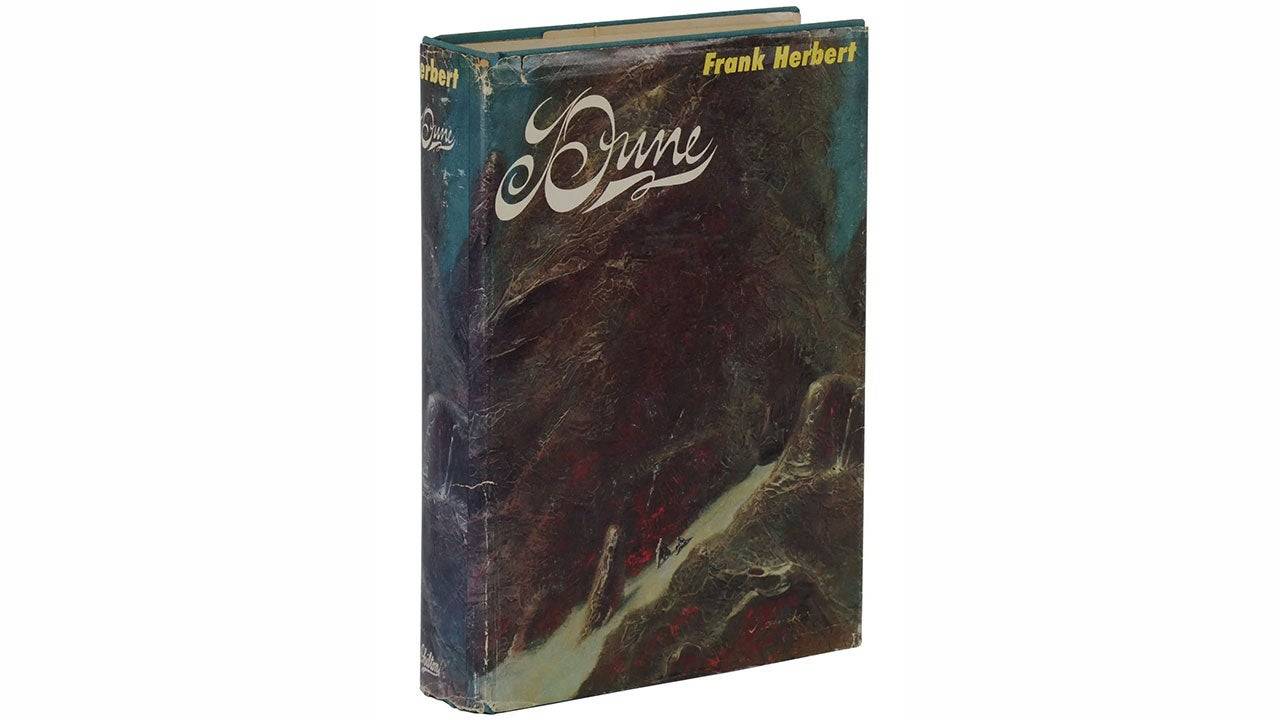

Scott, fresh off the success of Alien, inherited Frank Herbert's sprawling, un-cinematic two-part screenplay. He selected a handful of scenes but ultimately commissioned Wurlitzer for a complete rewrite. Like Herbert's and Villeneuve's versions, this draft was envisioned as the first of two films.

Wurlitzer himself described the project as incredibly challenging, stating that outlining the story consumed more time than writing the final script. Scott later confirmed the script's quality, calling it "pretty fucking good."

Numerous factors contributed to the project's collapse, including the death of Scott's brother, his aversion to filming in Mexico (De Laurentiis's demand), escalating budget concerns, and the allure of the Blade Runner project. Crucially, Universal executive Thom Mount noted the script lacked unanimous enthusiasm.

Was Wurlitzer's adaptation a cinematic failure, or simply too dark, violent, and politically charged for a mainstream release? A detailed analysis of the script allows for independent judgment. While Wurlitzer and Scott declined to comment, the script offers fascinating insights.

A Reimagined Paul Atreides

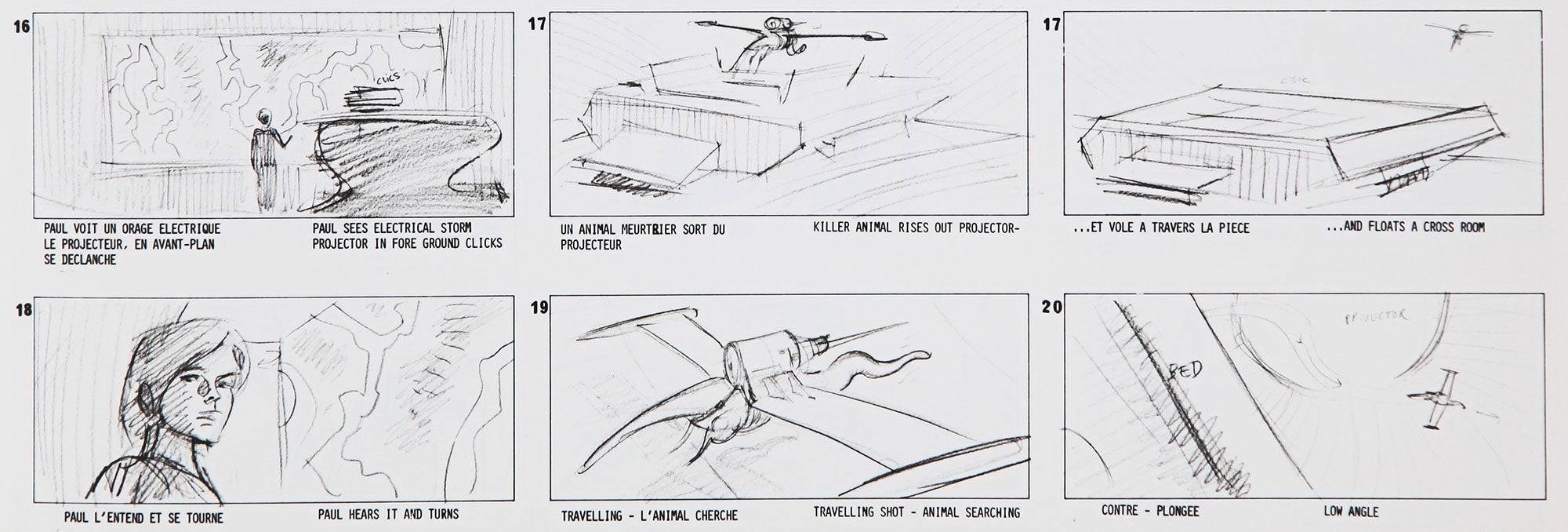

The script opens with a dream sequence depicting apocalyptic armies, foreshadowing Paul's destiny. The visual descriptions, characteristic of Scott's style, are strikingly cinematic. Paul, unlike Timothée Chalamet's portrayal, is a seven-year-old boy undergoing trials, showcasing his psychic connection with his mother, Jessica. While Lynch's version features similar imagery of pain and suffering, Scott's script emphasizes Paul's "savage innocence" and assertive nature. Stephen Scarlata, producer of Jodorowsky's Dune, notes the significant difference in Paul's portrayal, contrasting Scott's proactive hero with Lynch's more vulnerable character.

The script portrays a 21-year-old Paul as a master swordsman, and Duncan Idaho (replacing Gurney Halleck) displays a humorous demeanor.

The Emperor's Demise and Political Intrigue

The script introduces a pivotal twist: the Emperor's death, which acts as the catalyst for the events that unfold. The Emperor's funeral and the subsequent power struggle between Leto Atreides and Baron Harkonnen are depicted with mystical and visually striking detail. A key line, remarkably similar to a famous line from Lynch's film, highlights the importance of spice control.

The Guild Navigator and Arrakis

The script features a detailed description of the Guild Navigator, a spice-mutated creature, visualized as a unique, otherworldly being. Ian Fried, a screenwriter, highlights this as a missed opportunity in later adaptations.

The Atreides' arrival on Arrakis is depicted with a medieval aesthetic, emphasizing swords, feudal customs, and ecological concerns. The script underscores the planet's ravaged environment and the class disparity within Arakeen, drawing parallels to Gillo Pontecorvo's The Battle of Algiers.

A unique action sequence shows Paul and Duncan engaging in a brutal bar fight, showcasing Paul's early prowess. This scene, however, is criticized for potentially diminishing Paul's character arc.

The script also features a unique scene where Jessica levitates, and the Duke and Jessica decide to conceive a child, explicitly detailed in their dialogue.

The Deep Desert and Confrontation

Paul and Jessica's escape into the desert is depicted with intense detail, showcasing a thrilling escape and a crash-landing. The script emphasizes the harshness of the environment and the importance of Stillsuits. A confrontation with a giant sandworm mirrors Villeneuve's adaptation.

The script notably omits the incestuous relationship between Paul and Jessica, a significant deviation from previous versions that caused controversy. While this element is absent, a scene of intimacy between Paul and Jessica remains.

The Fremen encounter, the duel with Jamis, and the integration into the tribe are also vividly depicted, mirroring some elements of Lynch's film. The script culminates in a Water of Life ceremony, featuring a unique Shamanistic ritual and a sandworm encounter, drawing parallels to other works. The script ends with Paul and Jessica's acceptance into the Fremen tribe, setting the stage for future conflicts.

Analysis and Legacy

The script's portrayal of Paul as a more assertive and potentially ruthless leader contrasts with other adaptations. The ecological, political, and spiritual aspects of the story are given equal weight, unlike previous adaptations.

The script's dark and mature tone, along with its deviations from the source material, likely contributed to its rejection. The script's emphasis on ecological themes and political intrigue offers a unique perspective on Herbert's work.

The legacy of this lost Dune includes H.R. Giger's striking sandworm design and Harkonnen furniture, and the involvement of Vittorio Storaro as the intended cinematographer. The script’s themes of environmental destruction, fascism, and the awakening of the oppressed remain strikingly relevant today. Perhaps, in the future, another filmmaker will bring this unique vision of Dune to the screen.